- Home

- Loubière, Sophie

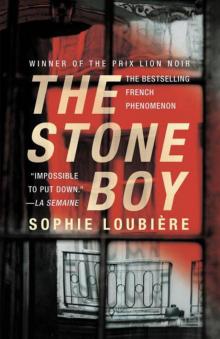

The Stone Boy

The Stone Boy Read online

The Stone Boy

Sophie Loubière

translated from the French

by Nora Mahony

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

Newsletters

Copyright Page

To my mother,

a woman of courage and dramas.

It is better to save a guilty man

than to condemn an innocent one.

Voltaire, Zadig, or, The Book of Fate

Living Up to Expectations

Each of us has heaven and hell in him…

Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

1

July 1946

The sun and wind were playing a lively game with the curtains. The little boy smiled up from his chair. To him it seemed like an invisible creature being tickled by this summer Sunday, playing hide-and-seek behind the jacquard fabric. When he closed his eyes, the child would have sworn that he heard chuckles of delight underneath the medallion print.

“Gérard!”

With his back straight and his palms either side of his plate, the little boy turned to look out of the window onto the garden. A glorious scent emerged from bunches of gladioli, lilies, and dahlias. Their astonishing colors sent bursts of light into the half-lit room. Peas rolled into the chicken gravy, swept aside by knife blades, indifferent to the lunchtime conversation.

Gérard went back to chewing, his nose in the air, hammering kicks against the legs of his chair. He wasn’t remotely interested in the subjects raised by his uncle, parents, and grandparents—wage claims brought on by a rise in food prices, the “teeny-tiniest swimsuits in the world,” an American nuclear test done on the Bikini Atoll in the Pacific, and a trial in Nuremberg.

“Goering is pleading not guilty. It makes your blood run cold.”

Gérard’s uncle passed the silver breadbasket to his neighbor.

“The defendants don’t feel responsible for the crimes of which they’ve been accused,” exclaimed Gérard’s father before biting down on a crouton.

The little boy had pushed the chicken skin into little balls back in his cheeks. Now he raised a white napkin to his lips, pretending to wipe his mouth, and slyly spat out the chewed meat. All Gérard had to do then was drop the napkin under the table. Like every Sunday since the end of the war, the cat would come later to erase all traces of his crime. But then, something disturbed the natural order of things. A voice rose across the crystal glasses.

“Daddy, last night I saw Mommy.”

Sitting stock still at her place with her back to the window, Gérard’s cousin smiled. Everyone’s gaze converged on the little girl with the thick hair cut short below her ears. A dark fringe stopped at her eyebrows, and her emerald-green eyes shone out below.

“She came into my room and sat down on the bed.”

Gérard froze. A breeze lifted the curtains, giving everyone at the table the shivers. His uncle blotted his moustache with the corner of a napkin.

“Elsa, be quiet, please.”

“You know what? She was wearing her flowered dress. The one you like so much, Daddy.”

Her grandmother let out a moan and waved a hand in front of her face as if to chase away flies.

“Elsa, go to your room,” insisted her uncle.

The little girl’s face was as pale as a bar of soap.

“She said you shouldn’t worry about her. Mommy is well. She says she sends you a kiss. All of you. You too, Gérard. But she doesn’t want her nephew to feed the cat under the table anymore; she says it’s disgusting.”

Gérard dropped his napkin. The contents shook out across his shorts, revealing his attempted sleight of hand. In the same instant, a slap stung his left cheek.

“I told you to stop that!” his mother scolded.

Tears filled the little boy’s eyes and his stomach hurt. He lowered his head toward his stained shorts, so he didn’t see his uncle get up from the table and haul his daughter unceremoniously off to her room. Elsa’s cries echoed in the stairwell. No one dared eat dessert. The St. Honoré cake stayed wrapped in its paper, much to the chagrin of Gérard, who was being pushed out onto the landing by his mother before he could even button his waistcoat.

“Would you hurry up? Stop dawdling!”

Gérard hated his cousin since she had gone crazy.

They don’t believe that you’re alive, but they’re wrong.

All I have to do is close my eyes to find you.

You’re wearing your pretty dress covered in flowers.

And you’ve tied a scarf in your hair too quickly.

I think that you’re kissing me, crying.

My cheeks smell of your kisses.

You walk so quickly that the train has already carried you away.

You’re going to come back. I’m certain that you’re going to come back.

It’s only a name on a list.

Daddy’s wrong.

They’re all wrong.

2

August 1959

The young man slowly locked his arms across Elsa’s chest. He held her tightly against his body, not letting go. Her eyes closed, the young girl kept her mouth open, as if she were at the dentist. She breathed like a puppy that had run about too much, her head bent back, her gingham blouse swelling. A sigh escaped her lips.

“Go ahead. Squeeze. Squeeze me tight, cousin.”

In Elsa’s garden, between the cherry tree and the chaise longue missing its cushion, Gérard felt confused. An overpowering sensation emanated from the young girl and her surroundings. The lawn seemed to be inhaling the young man feet first, the plum trees bending toward Elsa, holding out their ripe fruit. When he was with his cousin, the world seemed to shrink around her and her alone, erasing everything around them, leaving just the faintest outlines; Gérard could only make out the beauty of this incandescent girl as he swooned.

“The stars,” she said, her voice barely audible. “I can see tiny yellow stars. Squeeze again!”

Gérard’s arms tensed, responding to the plea in spite of himself. Then, suddenly, the gasping stopped. She collapsed. Her body slid against her cousin’s stomach and fell to the ground like a sack of laundry. The young man hastened to hoist her onto the chaise longue. He slapped lightly at her cheeks, moaned her name, and felt for her pulse, but he couldn’t manage to find it in her ivory-colored wrist.

“Elsa? Elsa!”

He brought his mouth to her lips to give her some air. There was no sign of life. Sobbing, he shook the young woman by the shoulders.

“Elsa! Answer me!”

He cursed himself for surrendering to the young girl’s capricious desires, for agreeing to play such an idiotic game with her, gambling her life for a thrill. But he hadn’t wanted to look weak in front of Elsa, so he had slipped his arms under hers and squeezed and squeezed.

“Elsa, please!”

As Gérard had often witnessed before, his cousin made a miraculous return from the dead with a cozy laugh, coughing, like a little girl recovering from being tickled. Toughened up by her years at boarding school, she had no doubt fraternized with girls—girls from good families—and broken the rules of her orderly upbringing. Elsa had snuck out and developed a taste for the forbidden, but there was nonetheless a casual grace about her, and she was as confident as a boy.

“It was delicious, cousin.”

Elsa grabbed Gérard by his shirt collar and pulled their mouths together.

“Do it again. Suffocate me in your arms. Make me die again.”

The touch of madness was irresistible.

Saint-Prayel School, Moyenmoutier

15 September 1961

Dear Daddy,

The students in my class are horribly clever, regardless of how Mr. Mohr goes on about

them. I’m grateful to them for making my job easier for me: I’m much encouraged by my first steps on the path to teaching. I believe that children have things to teach us about our capacity for understanding and grasping the truths of this world. They hide behind new words, ones they’ve barely learned, and I find it endearing.

I miss you, and the house, too. Here, I often go for walks. The forests are magnificent and I breathe in pure air that smells of ferns. Mommy would find the region too cool, though.

I have a comfortable little apartment just above the school that comes with the job, but I am fairly isolated and far from the town. Gérard doesn’t visit me unless he gets leave, which is rare. In Algeria he is mainly treating civilians, and tells me he is performing amputations on children. I think that Algerians aren’t just fighting for their independence; they’re starting a real revolution. It’s all anyone talks about around here. Sons, husbands—many of the men have left, and those who come back are demoralized or violent. They’ve all become hardened, and they put on an arrogant machismo. They have to learn to respect their wives and children again. Some have come back so burdened that they are physically hunched over, their shirtsleeves stick out from under their jackets, as if they were carrying stones in their hands.

Forgive me for writing about sad things again, but I have no one to tell other than a stray dog who pisses against my door. I chase him out of the playground regularly, as I don’t want him to give the children rabies. I hope that you’re well and that you don’t miss me too much.

With love and kisses,

Elsa

3

She was standing up in her room a meter away from her bed, staring at the ceiling. There was an odd noise, like a marble rolling along the floorboards. The noise stopped, and started again, this time like the shoes of a dancer called to the attic for a macabre ballet. The woman stood in the middle of the room, dressed in a nightgown, one hand running over her round belly.

Leave me alone. Leave me alone, please.

She had got up to drink a glass of water to improve her circulation. Then, when she was back in her room, she had opened the curtains, worried. With her face tilted toward the frost-covered glass, she looked out beyond the chestnut tree, looking around for someone, a shadow crossing the snowy garden, the memory of a floral dress disappearing around the corner of the street one spring day during the war. Then the noise happened again. A marble across the floor. Sashaying footsteps.

No. I’m begging you. Go away!

Elsa was standing still by the window, her skin taking on a bluish cast from the streetlamp. Her knees weakened and buckled, and she writhed in pain. Overhead, the noises started again, louder, in the rhythm of her contractions with each pitch and roll of her insides. She didn’t groan, didn’t scream, didn’t wake her husband.

Leave me alone! I don’t want to come with you! Not now!

It was two hours since the sun had withdrawn from her frozen feet. The noise of her fall had woken Gérard. His young wife was sitting in a puddle of blood. Elsa was giving birth.

22 August 1974

Gérard,

I can’t go on with your way of life anymore. Your absences are longer than ever. Seeing you come back late, neglecting your son and your wife, all so that you can take care of people other than us—people who aren’t suffering like I am—is not acceptable. To endure the weariness of a doctor who has reached his limit, to be subjected to your mood swings and your listlessness, is too much for me. I already know the scene; there’s no need to play it out further. Your plan to leave for Canada to take up your studies again and to specialize is a shining example of your egotism. How can you intend to dedicate your life to diseases of the heart when you show so little regard for my heart and that of your son? Did you even think of us, of what I would be obliged to sacrifice in order to follow you—my position as headmistress, for example?

I would prefer that you not return home again and that, in time, you rent a studio so that you can take stock.

This changes nothing about my feelings for you. I love you; you are the only man in my life and my son’s father.

I will explain the situation to Martin.

Elsa

4

Kneeling in front of the low table in the living room, the child unwrapped his present with the enthusiasm of a man condemned to death. The size of the item covered in forest-green paper was far too modest to correspond to Martin’s hopes. He had asked for a giant Meccano set and a chemistry kit for his birthday. The child held up the package: too heavy for a board game or a giant puzzle.

“Go ahead, Martin, open your present.”

His mother forced a smile through too much makeup. Her lipstick was like a dark purple rail track through the snow. The cider was too sharp and the chocolate cake needed more butter. Also wanting were Martin’s classmates: the little party couldn’t be held until the second Wednesday in January. There was no upside to being born between Christmas and New Year at all. It was usually impossible to get all of your friends together, the luckier of whom had gone skiing, and there was the disappointment of Christmas gifts being put aside for your birthday “unless your parents thought ahead,” which was never the case with Martin’s parents. So, the gifts that he received were rarely as impressive as those opened by his friends twice each year. Regardless, Martin’s mother had always held on to the idea that they should “mark the occasion.”

“A little party, just us. What do you say?”

Sitting on the big armchair in the living room, her knees together below her lilac wool dress, she looked like she was praying, her elbows bent, watching Martin’s fingers tear open the wrapping paper on his first gift. When he saw the encyclopedia, the child turned pale.

“Do you like it?”

“It’s not what I wanted.”

“It’s a useful gift. You’ll need it for your studies.”

“Yes, but it’s not what I wanted.”

“We don’t always get what we want in life, Martin. Open your other gift.”

“If it’s like the first one, I don’t want it.”

“Stop that. Go on, open it. It came from Galeries Lafayette in Paris.”

Martin pulled off the paper more quickly this time: maybe it was one of those wonderful toys he’d seen last week in the window of the big Parisian shop. Inside a gray cardboard box lined in cellophane, the little boy found a pair of mittens and a matching hat.

“It’s pure wool. You won’t be numb with the cold going to school in the morning with them.”

The hat was rust-colored with brown snowflakes embroidered on it. It was a ridiculous thing to put on in the playground. Martin looked at his mother, incredulous.

“Why did you buy me that?”

She leaned down to her son and caressed his face.

“Listen, Martin, times are hard, as well you know. Your father has abandoned us and I have to get by on just my own salary, so—”

“That’s not true! You’re talking rubbish!”

On the verge of tears, Martin threw the box and its contents on the ground, then ran out and shut himself in his room. His mother’s voice echoed up the stairs: “Come now, try to be reasonable, Martin! You need a hat much more than a Meccano set!”

2 April 1979

For the attention of the Director of the County Council of Seine-Saint-Denis

Sir,

Allow me to bring your attention to a sect that appears to be operating currently in Seine-Saint-Denis and with which I have unfortunately been in contact several times following a family tragedy.

This organization pretends to heal psychological damage and serious illness through nutrition and extreme fasting. Without a doubt, it involves cultlike behavior.

I had the opportunity to test several of their methods, including instincto-therapy, and I can report that the kind of practices suggested reduce the patient to an extremely fragile mental state. They allow the patient to become enthralled by what they are devoting themselves to, sometimes

causing social and family breakdown in cases where these were not the original causes of the patient’s isolation.

Certain individuals call themselves shamans, but they are nothing but frauds. That is the case for the person whose name and address is attached herewith. He is currently offering wildly expensive weekends at his farm in Neufmoutiers-en-Brie, where they are holding seminars on Peru on the pretext of helping his followers to reach, and I quote, “a quest for a saving self truth.” I think that this person is a crook. Personally, I have given him a great deal of money, thinking that he would help my father to overcome his cancer. Result: my father had a brutal relapse due to a massive vitamin B deficiency. I have already filed a report with social services and at the police station in my town, but the man is well established here and gains new followers daily in market squares across the region—that’s where he’s based, behind the counter at his supposedly organic fruit and vegetable stall.

Dreadful charlatans are hiding behind this façade of getting back to nature and alternative psychology. We cannot allow not only a great many adults, but their children, too, to be subjected to such danger. As the headmistress of a school, I know certain parents who are in thrall to this gentleman, and who swear by him and him alone to heal their relatives. I could not let such instances with medical and social implications go unreported.

The Stone Boy

The Stone Boy